Hard to believe it’s August already. It has been a busy summer in the employment law world while we have been away, and there is a lot to catch up on for Iowa employers. For starters, here is a re-cap of three of the summer’s significant court decisions and one notable but not so significant one. Almost all of these case are good news for employers. We plan to follow-up in coming posts with more details and analysis.

1. Who is a "Supervisor", and Why Does it Matter Anyway? Whether an employee is a supervisor can be important in many different contexts, but the one in Vance v. Ball State University (U.S. Supreme Court, 6/24/13) involved an employer’s liability for race based harassment. If the alleged harasser is a "supervisor", the employer in many cases is strictly liable for the harm caused by the harassment, regardless whether anyone else in management knew about it. On the other hand, the employer is not liable if the harasser is not a supervisor, unless management knew or should have known about it. According to the Supreme Court, a "supervisor" for purposes of determining legal liability for unlawful harassment includes only those employees who have the power to make tangible employment decisions, such as hiring, firing, reassignment, promotion, etc. The ruling in this case also applies to any other unlawful harassment under Title VII, such as sex, national origin, or religion. It probably applies to age and disability related harassment as well.

2. What is the standard for proving retaliation under Title VII: In University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center v. Nassar (U.S. Supreme Court, 6/24/13), the Court held the plaintiff must prove the employer would not have taken adverse action against the employee “but for” the employee’s engagement in protected activity. Before Nassar, some trial courts had applied a lesser burden on plaintiffs, requiring a them to prove only that the protected activity was "a motivating factor" in the employment decision. There is a big difference a "but-for" standard compared to "a motivating factor." With the latter, the employee must prove only that the unlawful reason played a part in the decision, whereas the former requires that it be the determining factor.

3. Punitive Damages are Not Recoverable under the Iowa Civil Rights Act. The Iowa Supreme Court so ruled in Ackelson v. Manley Toy Direct, L.L.C. (Iowa Supreme Court 6/21/13). Employers should breathe a big sigh a relief with this ruling.

4. Nelson v. Knight reprise. Remember this case from last December involving the Fort Dodge dentist who fired one of his assistants because he was attracted to her? The Iowa Supreme Court granted a motion to re-hear the case, which almost never happens. The court then issued a new opinion, but the result was the same—no sex discrimination by the dentist. The difference this time was three justices wrote a separate opinion the purpose of which seemed to be to limit the precedential value of the case going forward. As we stated after the first opinion, the Nelson case is not likely to have significant impact on discrimination jurisprudence. It’s not clear why the three concurring justice felt compelled to write a separate opinion after re-hearing.

him or herself.

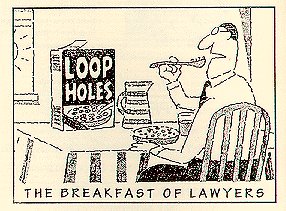

him or herself. Despite the strict enforcement of the administrative process, for many years there seemed to be a loophole in the

Despite the strict enforcement of the administrative process, for many years there seemed to be a loophole in the  discrimination even if the decision maker was not biased. It applies if there is evidence a non-decision maker acted with a discriminatory motive and caused the adverse employment action. The most common example is when the decision maker relies upon information or advice given by a biased non-decision maker.

discrimination even if the decision maker was not biased. It applies if there is evidence a non-decision maker acted with a discriminatory motive and caused the adverse employment action. The most common example is when the decision maker relies upon information or advice given by a biased non-decision maker.